Do we have enough battery materials?

Do we have enough battery materials on Earth to replace fossil fuels? A simple answer is no if we would use just conventional Li-ion batteries everywhere. But if we use several battery chemistries and can improve the lifetime, energy density and recycling of battery materials, then probably yes. At least I have a big trust in the battery community that we can do this together.

We know that we will need a lot of energy storage devices in future in case we want to get rid of fossil fuels completely. But it is not that simple to calculate how much energy storage capacity we need to replace fossil fuels. And even though we would be able to estimate the need, it is even more difficult to calculate the need for battery materials. This is since there are several battery chemistries available and we do not know which of them will be used in future and how much. And many common battery materials are used also in other applications. So, we should also take that into account.

Calculations about energy storage and materials need

I have not done calculations myself about the need for energy storage and battery materials in future. It is a huge task, including estimations for electrification of transport (electric cars, trucks etc.) and stationary storage for renewable energy (storing of energy from wind and sun). Luckily there are reports available, e.g., by the International Energy Agency (IEA), World Economy Forum, and a Finnish institute GTK, Geological Survey of Finland.

IEA and GTK have different estimations, especially related to the stationary energy storage. I asked the author, Simon Michaux from GTK, about the reasons behind the differences. Simon has used a 4-week energy storage buffer for wind and sun energy, which he thinks is still quite conservative. Some researchers have suggested even up to 12 weeks of buffer. IEA predicts much smaller need for the buffer, which is the main reason for the differences in the estimated energy storage need.

Even though there are differences, it is in any case a huge task to replace fossil fuels. The IEA report can be considered as the minimum, but most likely the need will be higher.

Availability of materials

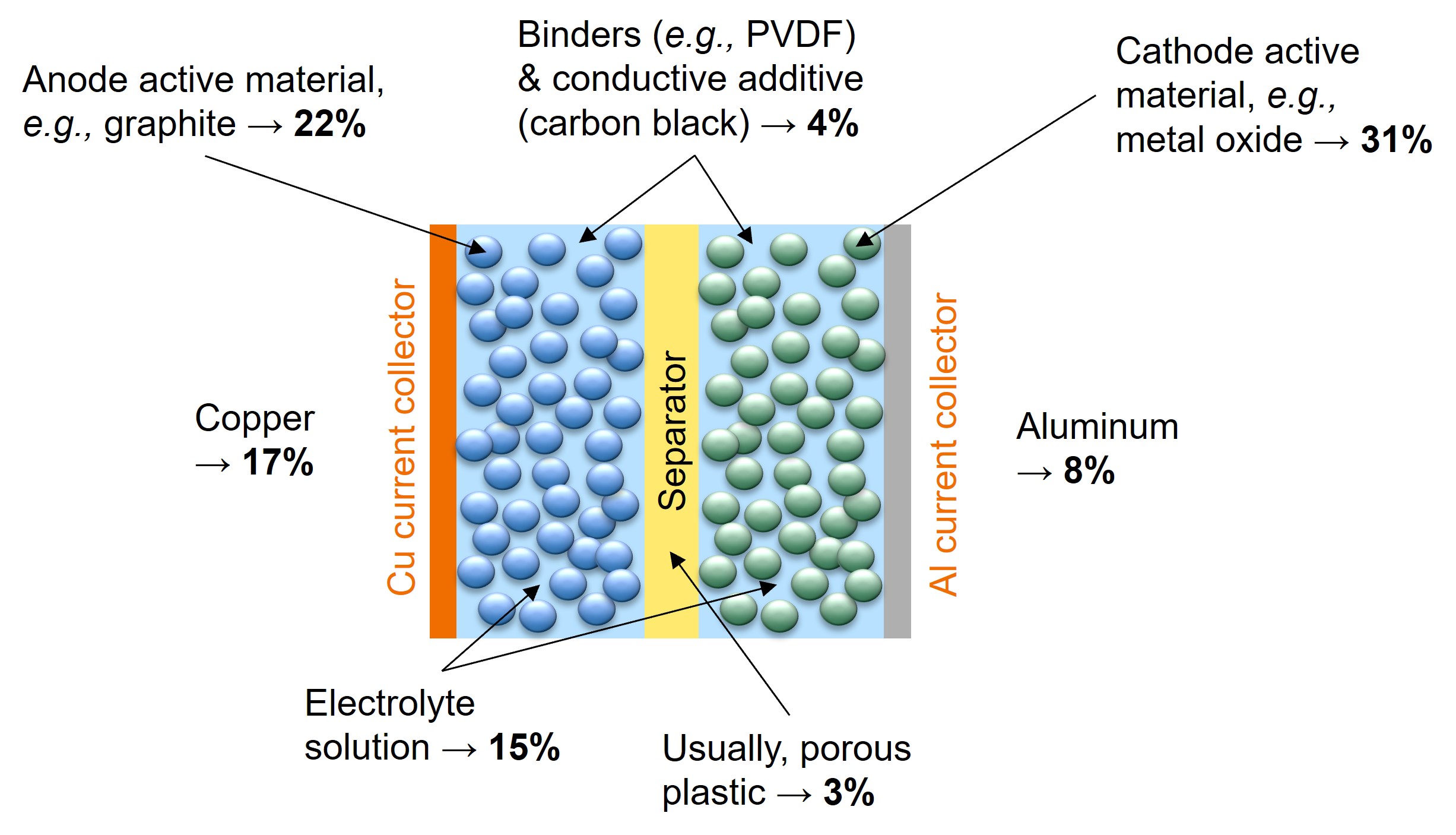

The most common battery type today is the Li-ion battery. A Li-ion cell consists of the electrodes, current collectors, separator, and electrolyte and has roughly the following structure and material amounts in percentage of weight:

The metal oxide used in the cathode is usually NMC, which contains nickel, manganese, and cobalt, in addition to lithium. However, other options are also available.

If we look at the common battery raw materials, and the very informative periodic table of elements that shows the material availability, we see a lot of similarities, unfortunately. For example, lithium, cobalt, graphite, nickel, manganese, and copper are needed in Li-ion batteries – and they are listed having limited availability, or serious/rising threat in supply.

Also, the European list of critical raw materials includes lithium, natural graphite, and cobalt. The already mentioned report by GTK contains information about the material availability as well.

All these reports have the same message. We will have problems with the battery material availability unless new solutions and chemistries are taken into use. In addition, the environmental and societal problems with mining are a concern.

This is all well recognized, and battery researchers around the world are working hard to find solutions to these problems. I will list some promising examples below, but more research efforts and funding are still needed to accelerate the work.

Different battery chemistries

One clear solution to cope with the increasing energy storage need is to use different battery chemistries. Li-based batteries, especially the coming generations, have high energy density. Thus, it is likely that Li-batteries will be used in applications, where energy density is important. This includes electric vehicles, as a battery with higher energy density can provide a longer driving range.

It is important to develop other energy storage solutions for applications that do not require very high energy density. This way we will secure material supply for each application. It is not even meaningful to use the same chemistry everywhere as the requirements vary as well. Some need to have long lifetime or cyclability, and some require ultralow cost, or extreme safety. Some applications might require fast charging, but other properties might not be so relevant.

Examples of beyond-lithium chemistries include Na-ion batteries, Mg-batteries, organic batteries and many more! It is also possible to increase the sustainability and material availability of conventional Li-ion battery components. For example, we can produce hard carbon materials from biomass by pyrolysis, which is one of our research topics at VTT as well. Bio-based hard carbon could replace natural (mined) graphite in the cells, and it is especially well suitable for Na-ion batteries. Na-ion is bigger than Li-ion and the conventional graphite structure is not optimal for the Na-ion transport. Hard carbon has more space between the graphene layers and will allow Na-ions to move more easily in the electrode.

Many of the EV producers, like Tesla, have also decided to use lithium iron phosphate (LFP) cathodes instead of NMC. LFP has lower energy density, but it does not contain cobalt or many other materials with limited availability. Anyway, it contains lithium. I have heard very different estimations about availability of lithium. There is quite a lot of lithium on Earth, but the easiest places for lithium mining might have been already found. Thus, it is not clear to me if it is possible to increase the mining activities enough in a sustainable way.

Note that it might be also possible to extract lithium from sea water in future. There is plenty of lithium in the seas, but so far it has been too costly to use it. And one of my colleagues just gave me this point of view: “Who knows what the effect on the whole ecosystem is if we start extracting significant amounts of lithium from seas”. A good question, and I think we do not yet have an answer for this.

What else we can do?

Producing more and more battery materials, even though still needed, won’t be enough to find sustainable solutions to fulfill the increasing energy storage materials need. Other needed actions include recycling and 2nd life use of old batteries. In addition, we can increase the lifetime and performance of batteries. This way we can store more energy with the same amount of (critical) raw materials. Battery 2030+ large scale research initiative, where I’m involved as well, is targeting just these actions. Within Battery 2030+, we are developing sustainable batteries of the future, with increased lifetime and performance, not forgetting the recycling and manufacturing aspects.

In summary, we do not lack solutions – we lack time. We also need more people to work in this field. That’s one of the main reasons I’m writing this blog: to inspire you to join us and to solve the energy crisis together 😊